A Primer on a System Call: Fork

Jack Garay

—April 22, 2020

The UNIX operating system process API provides a built-in functionality that allows us to create, pause, execute, or terminate a process. The code in this article is based in C, but if you're not familiar with it, feel free to continue as the code isn't cryptic enough not to be understood.

Before we dive in to the basics, let's first know what a process is. Courtesy to UNIX Internals: The New Frontiers: a process is the instance of a computer program that is being executed by one or many threads. Essentially, if we were to write our own program and would like to execute it, when we open that program, the operating system, under the hood, creates a process, assigns it an identifier, and then executes it on that process.

A process has a property we call PID (process identifier). This PID is useful in cases where we want to tell a process to either terminate, pause, or wait. For example when you kill a process in UNIX, you can run kill -9 <pid> in the terminal that tells the operating system to terminate that process with that specific PID.

Fork

fork() is a method used to create a new process. It works in an odd way if you think about it intuitively but bare with me, this functionality is powerful.

fork()'s return values:

- negative value on unsuccessful fork

- zero on success

- positive value when it has returned to "parent" or "caller" (will expound on this later)

int main() {int ref = fork();if (ref < 0) {// Fork failed} else if (ref == 0) {// Fork successprintf("I am child with PID: %d", (int) getpid());} else {// Parent starts hereint waitRef = wait(NULL); // Ignore me for nowprintf("I am parent with PID: %d, I have PID of: %d",rc, (int) getpid());}}

Notice how there is a parent-child relationship between processes in the code above. What happens is that, once fork() is called, a new child process is created from the calling (parent) process. The control flow of the child (duplicate) process starts after the invoking fork() command.

Once fork() is called, the operating system "copies" the original function's address space and creates a new process that is by essence a "duplicate" of it. And now it looks like we have two "simultaneous" processes running: one that is a clone (child), the other being the original (parent).

If we were to modify the code above slightly and put

int main() {char* sharedValue = "something";int ref = fork();if (ref === 0) {// Child has access to `sharedValue`printf("%s", sharedValue);} else if (ref > 0) {// Parent has access to `sharedValue`printf("%s", sharedValue);}}

The code above illustrates how sharedValue is shared through parent and child, and thus proves that whilst they are in different processes, because the operating system "copies" or "duplicates" the address space of the parent to create a new process, the child process still has access to the values defined within the parent at the time the process was created via fork().

When fork() is called, the duplicate process (child) starts executing right after the calling line.

int main() {// parent process starts hereint ref = fork(); // child process is created// child process starts herereturn 0;}

We can illustrate this, however hairy and tedious, in this example source code:

int main() {fork();fork();fork();printf("hello\n");return 0;}

The challenging part is counting how many "hello"s will be printed.

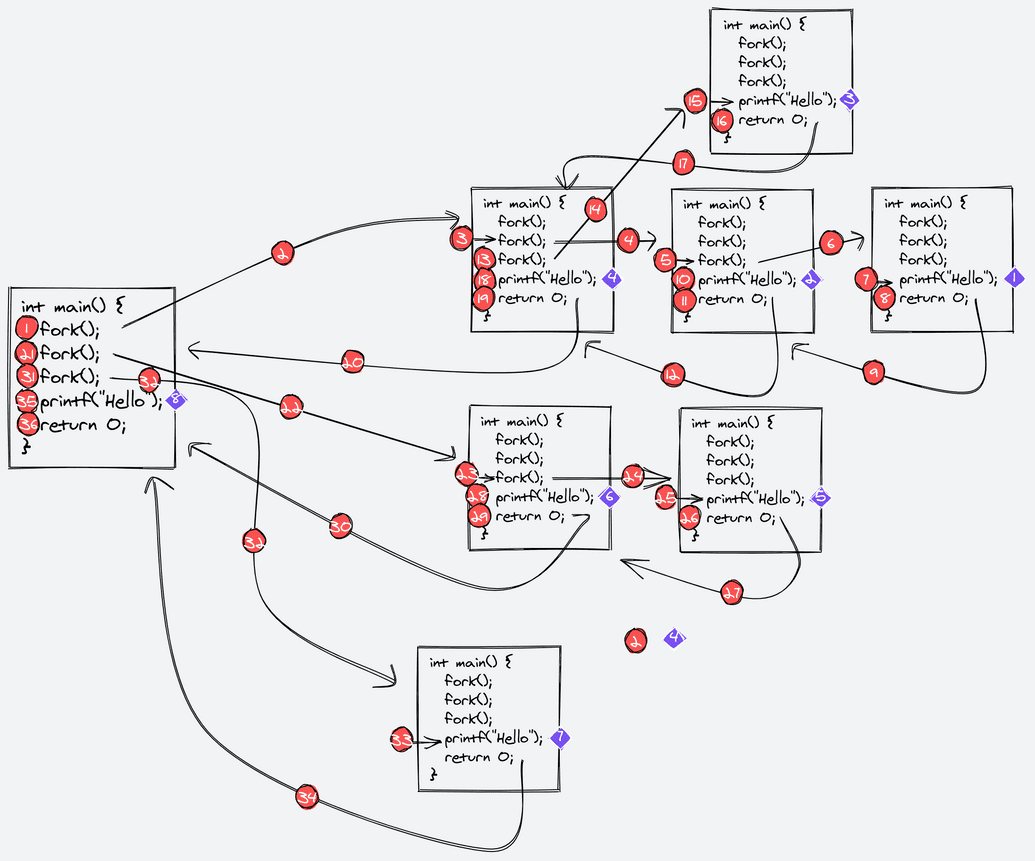

The process is hairy, hopefully the illustration below — demonstrating the control flow, and the "duplicating" of parent to child helps clear it up a bit:

At 1, the main process called a fork which created a new process at 2. Since the child process has a duplicate code of the parent, at 2, the statements in the process at 1 is still there, except it starts executing at 3 — line 2 of the child process — which is the statement after the the fork() that invoked it.

It's also important to note that the above illustration is not always the case with parent-child relationship. It's not uncommon for the parent process to finish before the child process. This is because processes are run by the CPU and are scheduled differently. So the sequence of events from the illustration is not the exact timing of events, but rather under the assumption that they run synchronously (which they don't). The takeaway of the illustration is to demonstrate the parent-child relationship and how fork() can create exponential number of processes (a parent can make a child, a child becomes a parent, and so forth).

int main() {int value = 0;int ref = fork();if (ref == 0) {// child processvalue = 15;// parent will not see this// new value// `ref` in this case is// the PID of the child process// that was created by the// line 2 int ref = fork()} else if (ref > 0) {// parent processvalue = 12;// child will not see this// new value}}

In as much as both of them share similarities, they now belong to separate address space (the child has a different address space but with similar initial values to parent). If a child process changes a variable, the parent process won't be able to reflect those changes as their address space are now separate. They also get different ref return values from the fork().

int main() {// parent starts hereint value = 0;int ref = fork();// child starts here// child process has ref of 0// so this condition is true// on child but not on parentif (ref == 0) {// child processvalue = 15;}// parent process has ref with a// positive number so this condition// is true on parent but not on childif (ref > 0) {// parent processvalue = 12;}}